methodologies

Inspired by the non-dualistic, syncretic oral musical traditions of weaver-dyer-poet-saints like Kabir Das and Shah Hussain for whom theory and practice were always aligned, our research methodologies emerge from technical aspects grounded in handloom weaving. The rootedness of these methodologies allows for a dialogic, reflexive and incisive inquiry into craft and artisanal matters.

zigzagging

Zigzagging is a movement of the shuttle carrying the weft yarn from side to side, that advances the fabric forward. As method, it involves translating, interpreting and speaking across and between registers, epistemologies and languages. We apply this to conversations that span different ways of knowing and registers.

-

Weavers who sing the songs of Kabir know that weaving knowledge exists in both the act of weaving and in the collective performance of these songs (known as Satsangs). The zigzag explores this relationship in order to understand how the complex knowledge practice of weaving spans these two very different registers.

-

Weaving and other craft practices are seen as a traditional or local form of knowledge as opposed to science which is seen to be global or modern. Zigzagging between these two ways of knowing, allows us to pose the question of epistemic justice. How do different forms of knowledge coexist, how are diversity and equity to be negotiated?

-

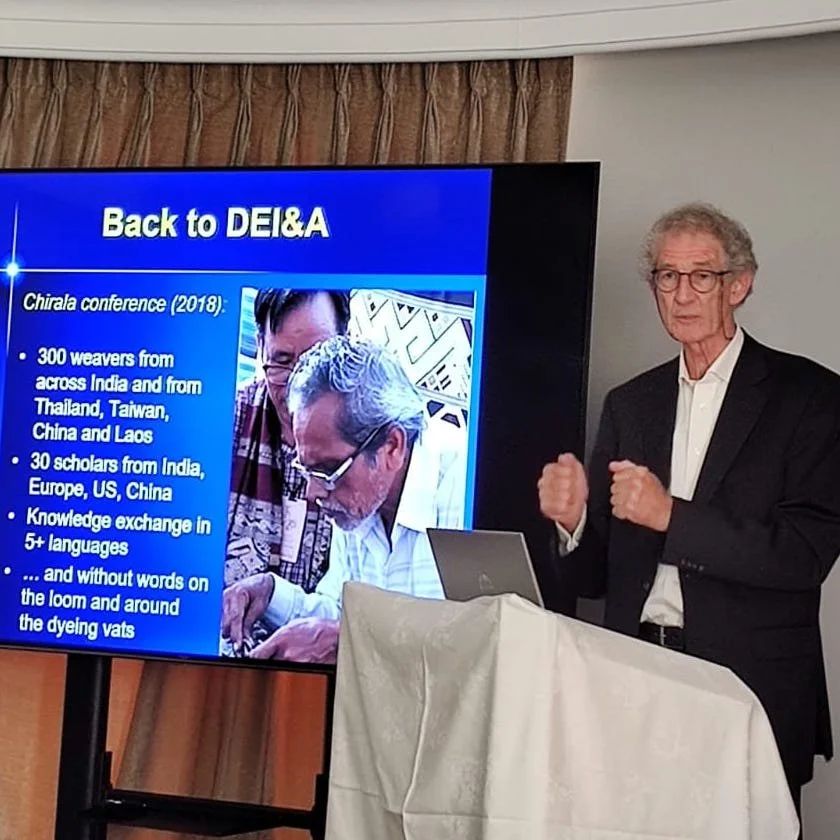

Working with practitioners who speak diverse languages necessitates translation and interpretation. Zigzagging in this context allows us to problematize the politics of translation, and make the intermediaries’ role more visible, by asking what happens to the untranslatable as well as that which needs no translation.

unweaving

The continuity of the weft thread allows the weaver to unweave by reversing the movement of the shuttle. To the untrained eye, this may look like the undoing of the fabric but unweaving decodes the weaving algorithm. We employ unweaving as a method to examine extant narratives and the processes that created them. This helps to make our research process reflexive and self aware.

-

To unweave is to be reflexive. We seek to make our research practice more transparent by cultivating an awareness of our role in the process. This effort is visible in our documentation that listens for the gaps in conventional narratives, in media criticism workshops where artisans reflect on how they are represented and in questioning institutional forms including NGOs, museums and unions.

-

Historicising is unweaving in time. We believe the primary participants to be the weavers themselves, and by unweaving historical narratives, we help handloom weavers understand themselves as subjects of history.

-

Reversing a particular action leads us to a new understanding of the nature of that action. We employ unweaving as a heuristic to explore unknowns which can be made more visible by retracing the action.

upturning

The logic of the loom can be read from the co-emergent patterns on the underside of the fabric, as well as the surface, upturning linear logics that see the two surfaces as opposites. We understand upturning as an act of inversion, that involves examining existing hierarchies and binaries by turning them upside down.

-

Craftspeople are often confronted with categories of a binary nature: traditional/modern, local/global, handmade/machine made, small scale/mass production and so on. We use the idea of upturning to question these binaries, in order to build a better public understanding of craft that can help craftspeople straddle multiple technological and social trajectories.

-

Forms of knowledge occupy distinctly hierarchical positions in contemporary society. For example, knowledge claims that are based on text are seen to be of higher legitimacy than those which involve embodied knowledge. We use upturning to show that in order for true equality to emerge diverse knowledge forms have to be acknowledged as equally legitimate.

-

The axis of western technological progress is often seen as a proxy for time. In upturning the direction of technological progress, we show how older technologies can be futuristic even as newer ones might foreclose previous possibilities.